As an historian I sometimes find myself on the defensive about what history is and what historians do. Especially when I teach the introductory US history survey to unenthusiastic undergrads, I find a depth of misunderstanding about what history is and is not. We don’t just discover, convey, and memorize facts. To the contrary, most of the historians I know are quite skeptical about “facts.” By contrast, we see the work that history does as twofold: we analyze change over time, and we interpret events by considering multiple perspectives.

First, we analyze processes of change over time. We seek evidence about how things were in the past, and we pay very careful attention to when and how things changed. Our interest in change over time means that we are very interested–sometimes even obsessed–with dates and chronology. How did ideas change? How did behavior change? How did policies change? When things did not change, why not? These questions are some of the key ones asked by historians.

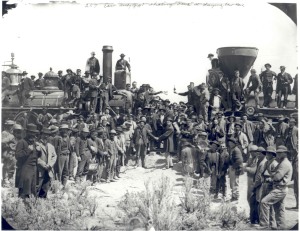

Second, we work from the assumption that there are multiple perspectives from which to understand anything in the past. People see and experience the world in very different ways. While some people have left voluminous records of their thought and action (say, for example, the US Congress), other perspectives are not always so well documented in the historical record (say, for example, the voices of Chinese workers building the transcontinental railroad). We analyze evidence to find the common patterns of thought, action, and language. We compare and contrast differing perspectives. We look for evidence that reveals how events might have appeared to people whose experiences were not well documented in existing archives.

History teachers at all levels have a hard time teaching these skills, as opposed to the rote tasks of memorization that students have come to expect from their history classes. What might this process look like in the elementary grades? How might we invite students to understand social and cultural differences in historical context? How might we encourage them to think about history as a process of change over time?

Two books that my family has on our shelves offer instructive examples for what this might look like. Coolies by Yin, illustrated by Chris Soentpiet (Puffin Books, 2001) and My Uncle Martin’s Words for America by Angela Farris Watkins, illustrated by Eric Velasquez (Abrams, 2011) are two very different books, with a few features in common.

First, and most importantly, both books begin with the present.

Coolies begins with a young Chinese American boy and his grandmother in the present. They’re celebrating the Ching Ming festival in which they honor their ancestors. The first illustration shows them in their living room. The large television, their contemporary clothing and furniture all mark the scene as contemporary. Yet their ethnic identity is also marked by the Chinese-style statues, decorative flourishes, and ceremonial shrine on the table. The grandmother presents the remainder of the story as a tale of “our ancestors,” so that the boy will not forget. The book ends with the pair completing their ceremony of paying respect to their ancestors. When I read this book out loud, I sometimes ask my kids to point out the things they notice that show us that these scenes take place in the present.

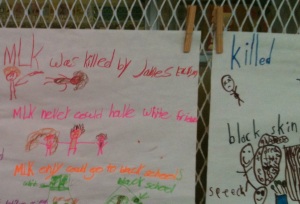

My Uncle Martin’s Words for America also begins with a child, Martin Luther King’s niece, who narrates the story. The first two pages of her narrative anchor the reader in contemporary African American achievements, before moving back in time to describe King’s activism. “Before America elected its first African American president…before African Americans became astronauts, or Hollywood directors, or billionaires, America was a very different place.” I really like this approach, since it does not foreground the violence or disrespect of the Jim Crow and Civil Rights eras.

Second, both books name specific past injustices and describe concrete responses. In Coolies, the brothers Shek and Wong join with other workers to protest poor work conditions and pay. Though the protest is unsuccessful, the pair perseveres in their loyalty to each other and their family back in China. My Uncle Martin’s Words for America describes several key protests in which King participated, and presents them in chronological order. The book draws a connection between public protest and a key legislative or judicial change that it informed, and it uses those stories to highlight King’s “Words”: love, nonviolence, justice, freedom, brotherhood, and equality. The information is then summarized in a chart at the end of the book. The book thus argues, in a way that’s appropriate for young people, that a combination of well-articulated ideology, public protest, and elite legal action combined to change Jim Crow law and practice.

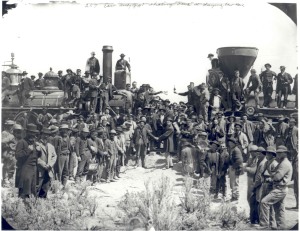

Finally, the illustrations in each book position the viewer/reader to see the story from a particular perspective. Velazquez’ illustrations in My Uncle Martin’s Words for America consistently position the viewer in the same plane as the protesters and the police. We are all on equal footing. Yet the viewer does not see the world from the viewpoint of the protestors–we are watching them. The illustrations in Coolies also position the viewer on the same plane as the workers. Coolies has one particularly powerful image that recenters the historical narrative to include Chinese Americans. In 1869 newspaper photographers widely circulated images of the celebration of the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, Utah. Notably, despite the arduous labor performed by Chinese workers to complete the railroad, and the fact that many of them who died in the process, most images from the time omit their presence.

Coolies redresses this visual absence. Soentpiet’s beautiful painting reimagines this scene from the perspective of Wong and Shek, who share in the pride in this accomplishment. The image literally reframes and recenters the story of the transcontinental railroad, so that it is about the people whose labor was crucial to the project, and their bonds of family and affection.

As a last note, I appreciate how Coolies quietly addresses the history of the word “coolies.” Cooly or coolie was a commonly used word in the 19th century to refer to low-wage workers from Asia, and it had an insulting, derogatory connotation. The book sidesteps the major legal discrimination leveled at Chinese between the 1860s and the 1940s, though it makes clear that Chinese workers were looked down upon by many in the United States. Yin introduces the term “coolies,” but never uses it as part of the narration. Instead, Shek and Wong are called by their proper names and their peers are collectively called “workers.” Coolie is also never used as a self-identification by Shek or Wong. In fact, it’s only ever used by the white labor bosses when they make demands on the workers. This is an analysis that older elementary students could probably make on their own with appropriate prompting.

The past can indeed seem like a foreign country, especially to young people who have little connection to the topics or groups they are studying. By offering young people only snapshots of the past without an anchor in the present we risk essentializing and stereotyping, particularly when we present histories of people of color. If Yin had tried to tell the story of Chinese workers without framing the story in the present, students might come away thinking that all Chinese are or were “coolies.” But the framing device prompts us to ask how Chinese Americans moved from being reviled workers in the 1860s to being an ethnic middle class in the 1990s. Though there is a lot of history between these two points in time, the book suggests that people like Shek and Wong were active agents in creating the stories that link the past and present. We need to offer young people tools to analyze not only how things were different in the past, but how things changed. When we teach them about inequality and prejudice and difference in the past, it’s worthwhile to take the time to meditate on how, why, and whether things are different now. What changed? How did it change? If people did not like how they were treated in the past what kinds of action were they able to take to make change? What has not changed? Why not? Whose story is being told when we study history? Whose story is not being told? And how can people here and now use the past to imagine more equitable futures for their families and communities?